Here we designed 3 types of units, fabricated 213 PETG components, and made an experimental pavilion attempting to explore the ability of thermoforming to program memory into sheet plastic.

Architects: Hanxi Wang, Charisse Foo

University: Cornell University, New York

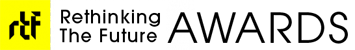

We discovered that thermoforming allowed sheet plastic to acquire a new resting state after deformation, and to always flex back to this deformed state. A simple curvature in one direction gave a plastic unit elasticity in that direction and rigidity in the other. We developed more complex doubly-curved surfaces to achieve a suitable combination of both flexibility and rigidity.

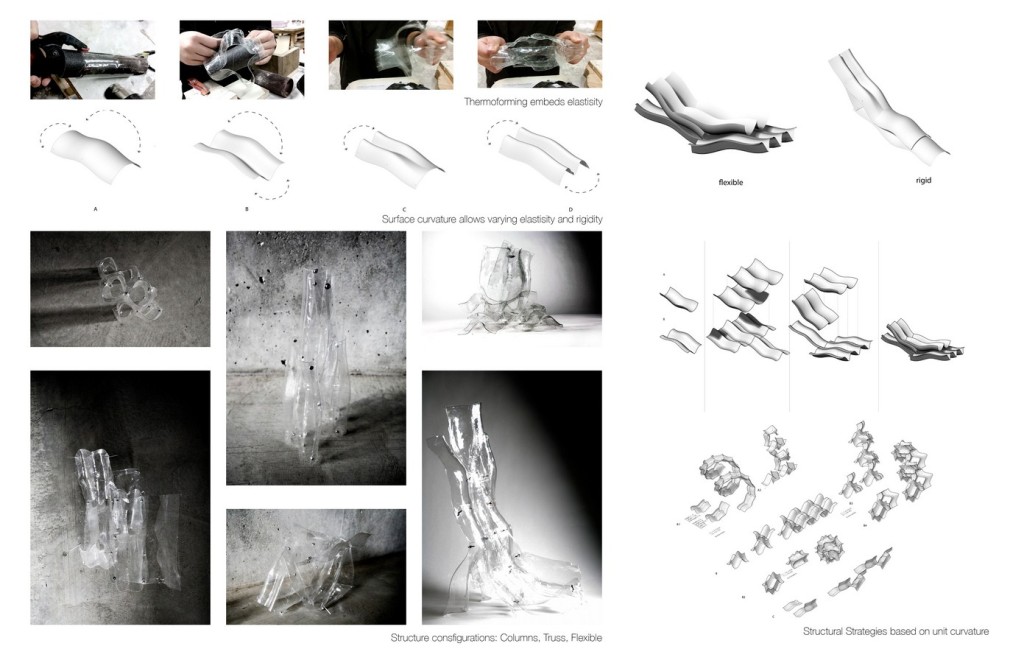

With a rectangle, a trapezium and a square, we tested multiple ways of using a ‘pinching’ aggregation to develop form, with varying degrees of structural strength. This method in combination with the embedded elasticity within the individual units allowed for a kind of ‘stretchy-ness’, which acted as pre-tension and allowed the final installation to rest in a state of self-adjusting equilibrium.

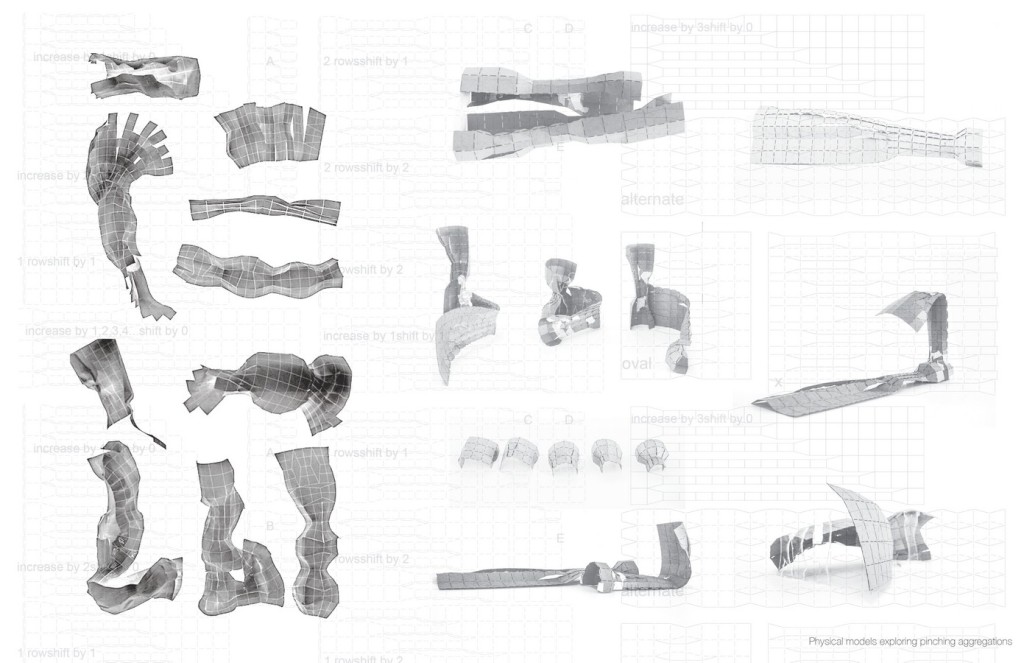

We investigated the types of forms possible with this system of aggregation: testing the limits of how drastically the structure can be pinched together or released, methods of weaving, methods of forming spheres, spirals, towers etc…

While exploring different global forms, we also worked to optimise the thermoforming fabrication process. We eventually produced more than 300 units reliably, quickly, and consistently, using 3 different sets of CNC-milled molds.

The final global form houses three structural systems: a thin, rigid column formed by triangulated units, a larger, softer, occupiable tubular column that expands out and cantilevers at the top and a series of mobile strips forming an arch between the two.

In exploring the structural and material properties of plastic, we were very much intrigued by the the spatial and visual experience of a transparent and distorted enclosure. With continual spatial, material, and visual deformations, the pavilion is both rigid and organic, open and closed, as much a window frame as it is a wall.

Due to the strength of the material, the embedded flexure of the unit surface, and the permanence of riveted connections, the structure is interactive, changeable, but not breakable.

[author title=”Hanxi Wang” image=”https://www.re-thinkingthefuture.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/hanxi-wang.jpg”]Hanxi Wang is currently an architecture student in her fourth year of study at Cornell University, New York. She is inspired by innovative and efficient uses of material and her work experiments with them to create productive, nuanced and intricate spatial experiences. Hanxi was born in Tianjin, China, and spent her teens in London, UK. She has worked at various international design firms such as Grimshaw Architects, Junya Ishigami + Associates, and NADAAA inc.[/author]

Charisse Foo

Charisse Foo grew up in Singapore and is currently studying architecture at Cornell University, New York. She is most excited by the intersection of architecture, art, and code, and the multitude of ways in which everyday visual and spatial environments can be transformed.

Fluid Pavilion was previously featured in ArchDaily’s ‘The Best Student Work Worldwide,’ August 2015.