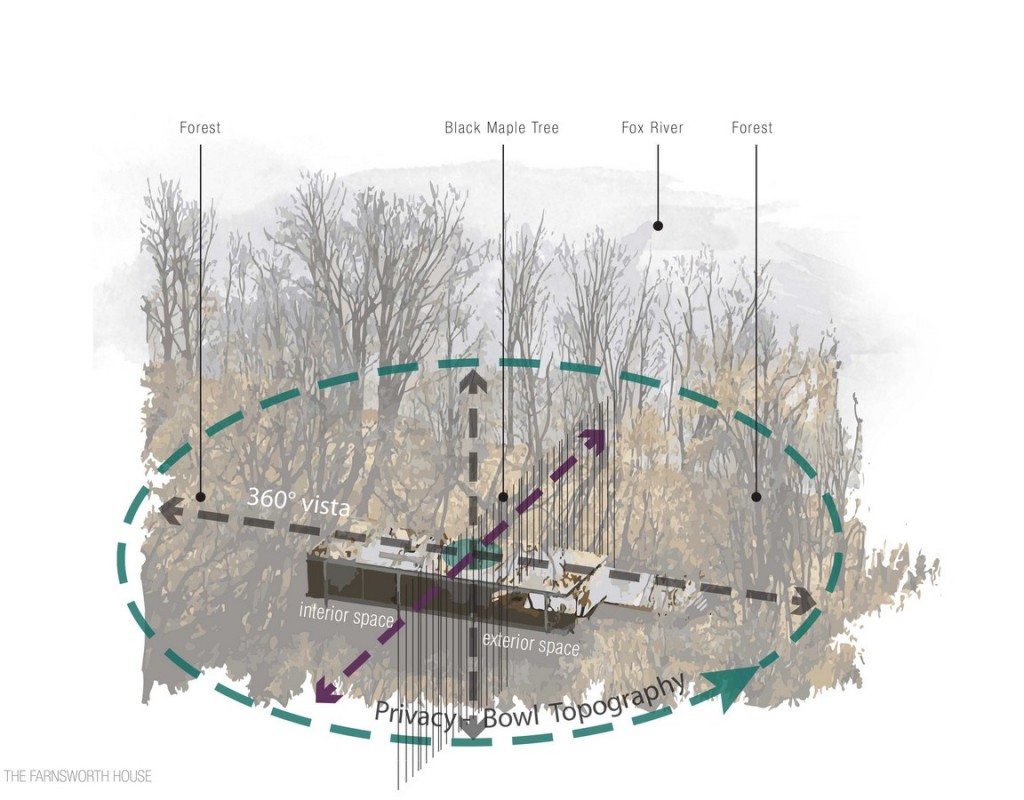

The Farnsworth House has always been a modernist architectural icon. Mies’ floating white steel frame and glass walls blend the exterior with the interior, attracting many visitors to the house since designated a National Historic Landmark in 2006. However, with the increase in urbanization and stronger rain seasons, the interior is consistently being damaged by flooding. Preservation of the house has become the main goal and various methods of moving the house have been proposed. Our proposal takes it a step further where not only the house is saved, but the entire site is reconfigured to work aesthetically, technically, and ecologically. The design takes aesthetic principles from the past, studies issues of the present, and reconstructs them into sustainable solutions for the future. By redefining the idea of preservation, the Farnsworth House becomes more than just an architectural icon; it transforms the entire site into a functioning system that will attract and educate visitors year round.

Team Members: Daniela Martinez, Diana Alcantara, Julianne Pineda, Yaneli Monjaras

Moving Mies

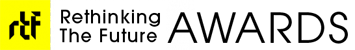

The Farnsworth House, located in Plano, Illinois, is seen as one of the best representations of modern architecture throughout the country. Located about two hours from Chicago, the house stands in a clearing surrounded by forests and faces the Fox River to the south. Designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe for Dr. Edith Farnsworth, the house acted as her weekend getaway from its completion in 1951 until it was sold to Peter Palumbo in 1971. Because Farnsworth is located in a floodplain, Mies designed the house to be elevated from the ground and look like a white steel frame floating in the landscape. The glass walls blur the division of the interior and the exterior space where visitors feel as if they are lifted out of nature but still connected to it. Mies considered the landscape as an extension of the architecture and Palumbo described the relationship between them as “an aura of high romance.”

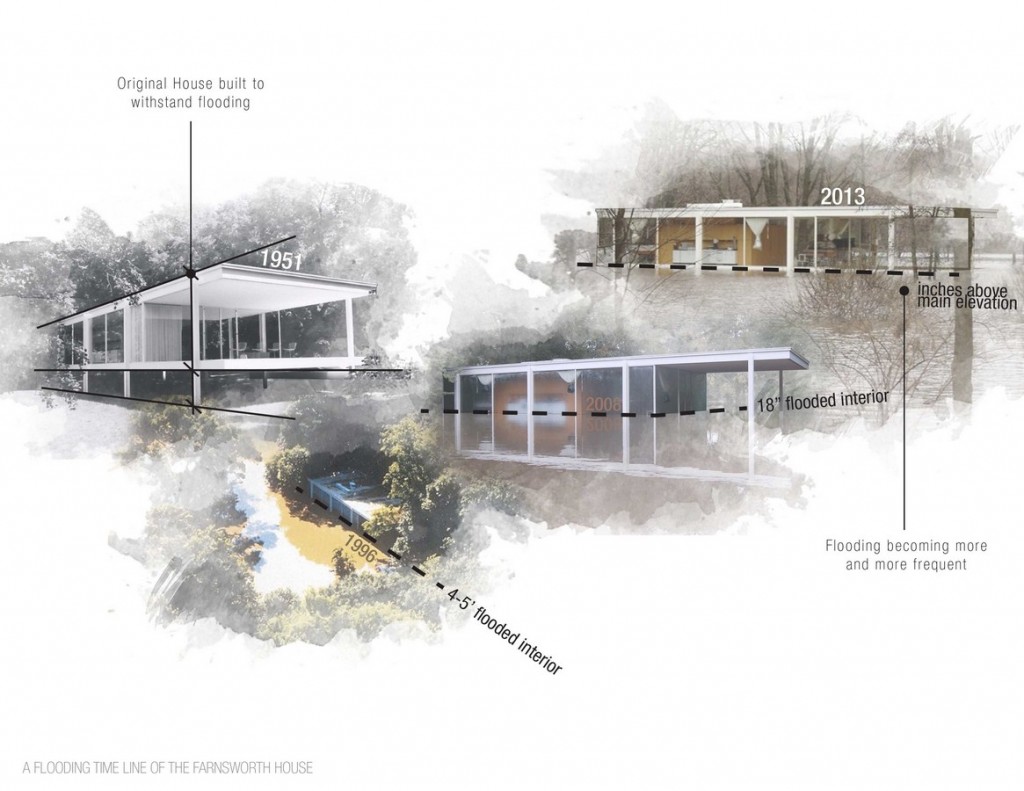

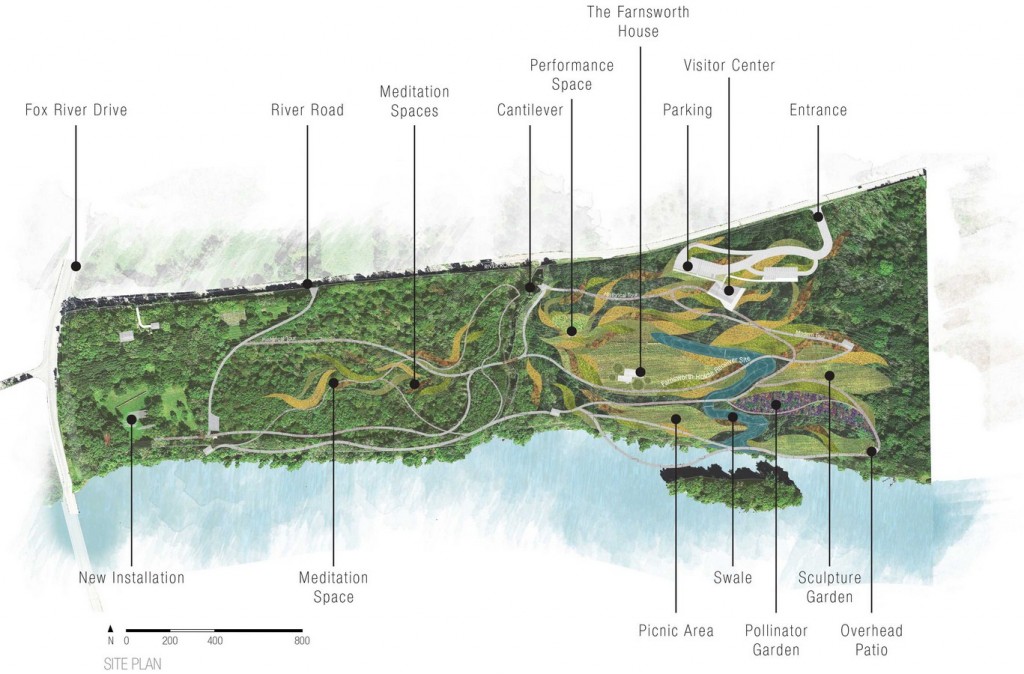

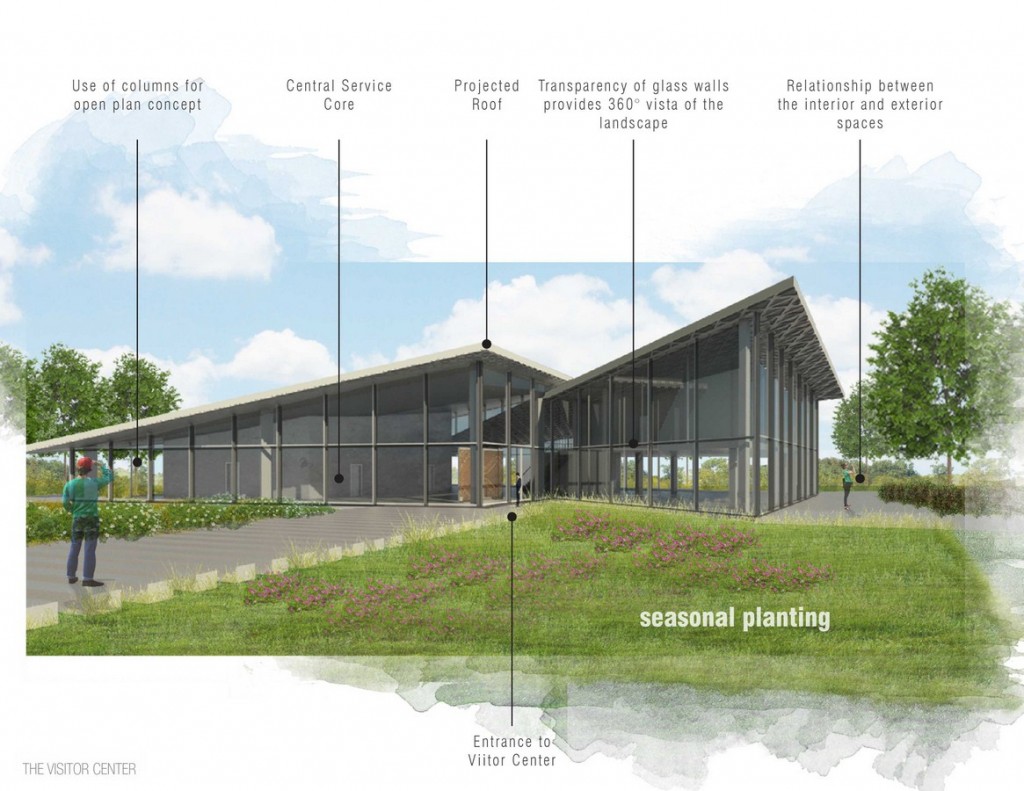

Relocation of the Farnsworth house became imminent due to higher rain runoff and stronger storms that raise the Fox River to a level that damages the interior of the house. Additionally, the desire to expand programs and services at the Farnsworth have resulted in the necessity of a new visitor center with a greater capacity to shelter more activities and visitors. This proposal moves the house to a new location and recreates the landscape to mitigate flooding while creating new environments that change every season. The new visitor center contrasts the house, but still alludes to it, and acts as the gateway into the new site.

Integrity of Feeling

While studying the area, several elements from the existing site were sought after for a receiver site. Major elements surrounding the house are Fox River Drive and the river itself. When transferring the house to the cornfield, the same conditions were met with Rob Roy Creek and relationship to the river was kept as true as possible without compromising views or creating extreme slopes from the house to the river. Although there is a geographic change, the same curvature and proximity to the river allows for a mimic in the original setting. Because of the distance to the river, in order to prevent flooding, a fill of 9 feet is necessary to prevent interior damage.

Re-grading the cornfield is key to flood mitigation for the receiver site. Directly around the new site for Farnsworth, the topography is transformed to create the bowl condition and keep the feeling of privacy similar to the original site. The house sits at the 573 elevation and still allows the pad to be flooded without destroying the interior. The rest of the cornfield is graded into terraces that step down towards the river. These terraces provide a more controlled flood pattern while also breaking up the spaces for more specific programming.

One of the main features of the original 1951 site is the black maple tree that sat right in front of the house. It brought shade directly into the house during the summer months and enhanced the direct relationship to nature. Replanting the tree in both the original site and receiver site will bring back the integrity of design and of feeling. In addition to this replanting, all of the Lanning Roper landscape as well as the forested area to the west of Rob Roy Creek and along the river are maintained. Keeping the ecology of the area was of upmost importance, so majority of the existing planting is undisturbed.

Redefining Preservation

More than recreating the original site, this proposal challenges the idea of preservation by transforming the elements to build a landscape that is both aesthetic and ecological and works with the architecture to create an educational experience from beginning to end. As previously stated, re-grading the cornfield helps control flooding patters; and with conjunction with planting design, both components produce environmentally sustainable design. Again, the landscape is graded in terraces planted with native plants that help dig further into the ground so that more water can be infiltrated. Additionally, the large swale that runs down the site is planted with cleaning plants to collect, clean, and redirect the water.

Although the planting design strategies take from both the Mies era and the Roper era, application of sustainability practices to these principles take them from being solely aesthetic to environmentally sensitive design. The seasonal pools Roper used are scaled up and drift across the entire site. These

drifts hold native plants to promote local wildlife habitat. Three different types of circulation are used throughout the site – elevated, ground level, and depressed – in order to create different user experiences. Two main types of paths run throughout the site, the tour path and the wandering path which both come off of the visitor center. The tour path is mainly ground level circulation and is 10’ wide to accommodate for tour groups. The wandering path moves mainly along the river and through the intimate spaces and along the creek. The river walk runs along and above the river to move the people close to the water. It begins in the east most picnic area and moves all the way to the original site and is lined with three pavilions, at both ends and in the middle.

The proposal for the original site keeps the Lanning Roper landscape intact as the vacant footprint of the Farnsworth transforms into an outdoor exhibition space. Slabs of concrete outline the house and extrude at various heights to create seating and enclosures. The memorial of the site is divided into three layers representing Dr. Farnsworth, Mies, and Lanning Roper. Dr. Farnsworth and her contribution of the original site is represented by the replanted black maple tree, which was crucial for the placement of the house. Underneath the tree sits an empty Miesian chair to allude to Mies’ time spent on the site. The larger Roper landscape is maintained to designate the Palumbo era.

Four main trees surround the Farnsworth in its new location that mimics the original. The trees are in the same positions as the original site. However, different species are used, each representing one of the seasons. To the west of the house are fields of seasonal plantings and to the east is the swale running down the slope. More than just an object in the landscape, the house and surrounding area will be programmed to hold events, concerts, or art showings.

Daniela Martinez

Daniela Martinez Hernandez is an Architecture undergraduate student at California State Polytechnic University Pomona, and she will graduate in June 2017. She is also pursuing a Regenerative Studies minor to understand the effects of Architecture and construction in the environment, and to learn to design in a sustainable manner. When designing, she likes to explore the influence of new designs on the existing built environment and social context. She also enjoys graphic design and exploring the relationship between graphical representation and Architecture.

Yaneli A Monjaras

Yaneli A Monjaras is a student at the California State Polytechnic University of Pomona, she is in her fifth year studying Architecture. She was born and raised in Orange County, but traveled in and out of the country throughout her young life. This much traveling allowed her to experience a variety of architecture. Her inspiration comes from the different culture, society, and needs. This is what composes her desire for architecture. She is excited for a Master in Computer Science to help her with what is coming next in architecture, technology.

Diana Alcantara Ortiz

Diana recently graduated from Cal Poly Pomona pursuing her Bachelor’s Degree in Landscape Architecture. Her journey in Cal Poly Pomona allowed her to discover the field of landscape architecture; where she learned the importance of creating better and more sustainable landscapes that will benefit both, nature and people. Participating in different study abroad programs enabled her to learn and experience different cultures and scenarios that increased her comprehension of different physical contexts in diverse settings. Currently, she is a Design Intern in the San Francisco Department of Public Works. Working in this position will contribute in her journey of excelling the relationships between the built and natural environments. It will also allow her to apply all the skills learned and wisely use the available resources to meet human needs and nature.

Julianne Pineda

Julianne Pineda

Julianne Pineda recently graduated from California State Polytechnic University, Pomona with a Bachelors of Science in Landscape Architecture. After studying different types of design, her passion falls into urban design, where one is able to create networks of environments to build better spaces for people and the community. Throughout her years in school, she has traveled to many cities from Portland to Santa Fe, even to Beijing, China, where she worked with architecture, landscape architecture, and urban planning students to design a network for green spaces for Beijing. Julianne believes that environmental design should be centered on the people. Her goals are to design spaces for people to create lasting experiences, pulling them back to that place again and again.